October 2017 | BIPS Research Grant

When I came across this description of Persian manuscript Or. 11519 in a British Library catalogue, my interest was piqued: “Or. 11519 Selected poems (mostly kasidahs) of Khvājū Kirmānī, apparently once part of a majmū‘eh of 500 f. xvth century. 66 f. 30.3 x 21 cm” [Source: G.M. Meredith-Owens, Handlist of Persian Manuscripts 1895-1966 (London, 1968), p. 63].

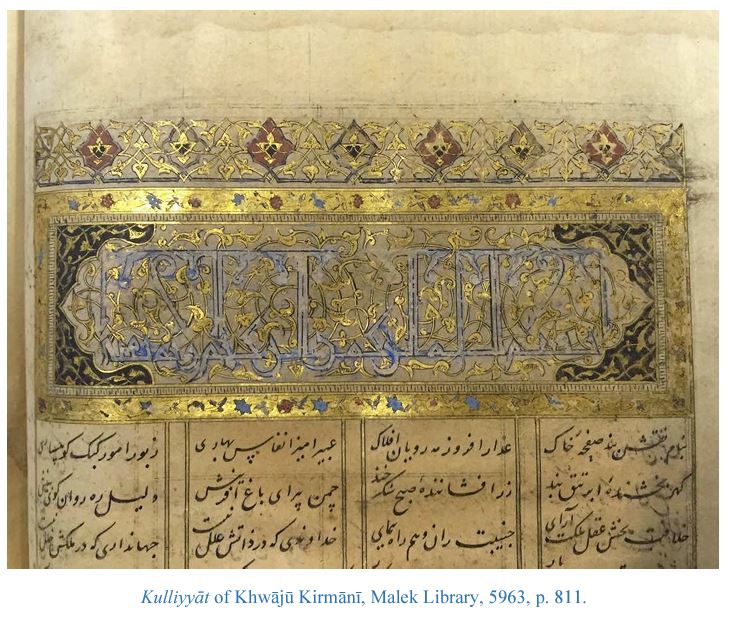

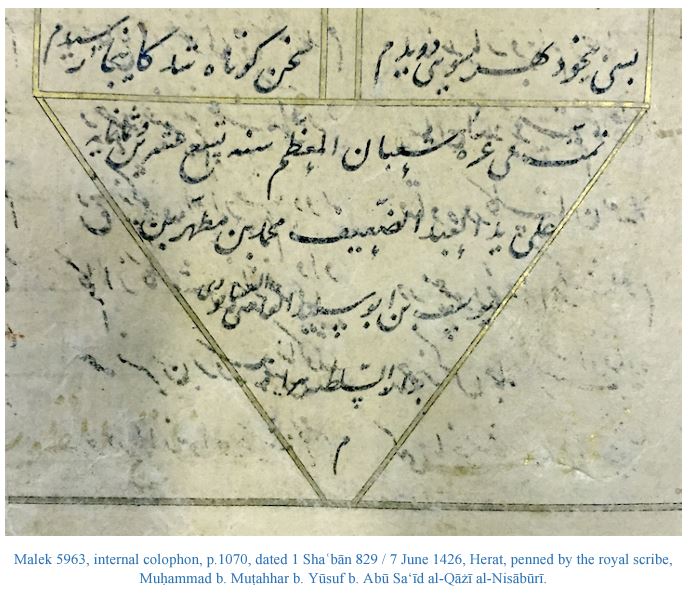

At the time, I was writing up my doctoral research into 15th century Persian book production under the patronage of Prince Bāysunghur in his atelier in Herat, modern day Afghanistan. I had discovered that the most complete extant early manuscript of the complete works of Khwājū Kirmānī (died c.1352) was almost certainly produced under Bāysunghur. For the scribe of Tehran, Malek 5963, dated 1426, I had identified as one of the atelier’s senior scribes, Muḥammad b. Muṭahhar, who also copied other important manuscripts for Bāysunghur. The Kirmānī manuscript, Malek 5963, is an exquisite example of Timurid royal book production, now sadly slightly defective at the beginning and the end.

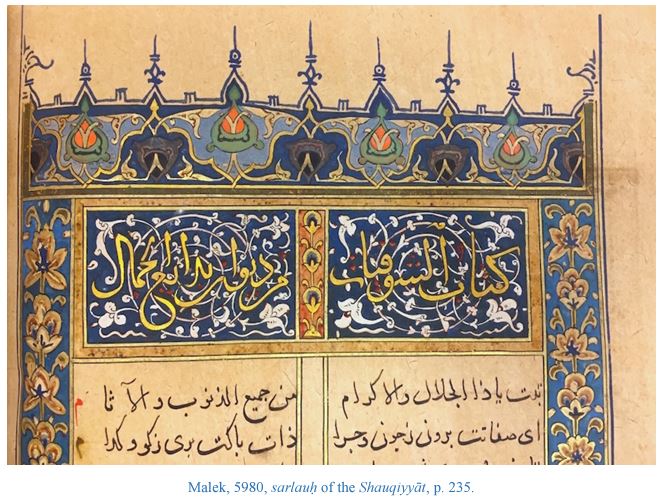

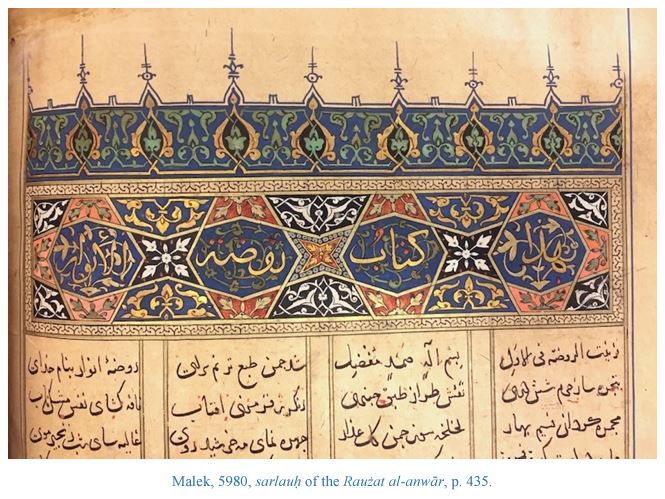

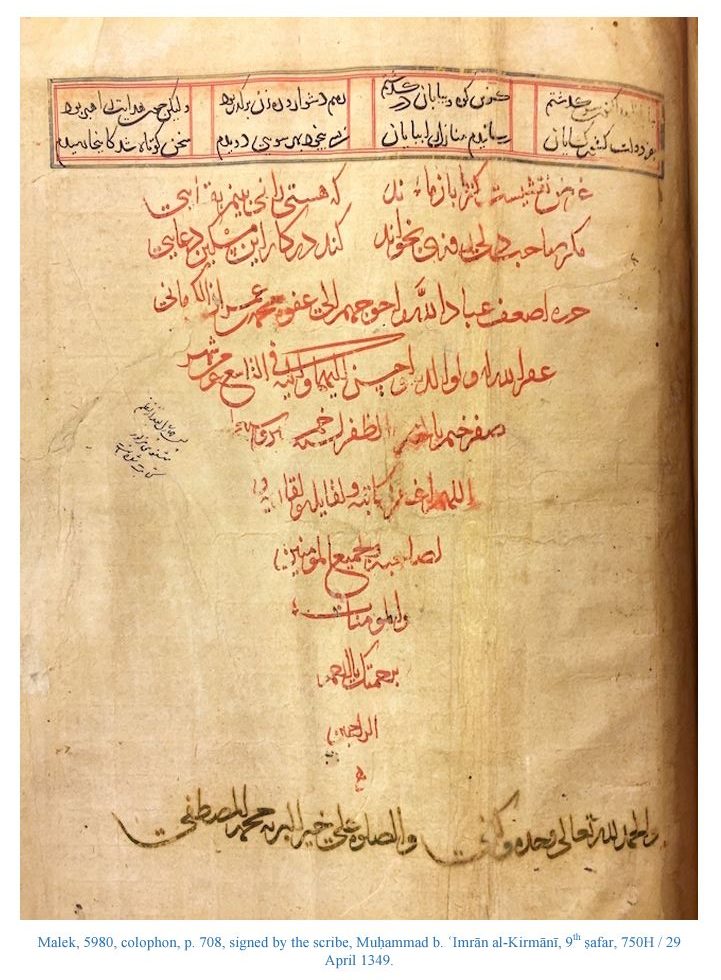

In order to verify the completeness of the Bāysunghurī manuscript, bar the minor losses at start and end, I had compared its contents to the oldest known Khwājū Kirmānī manuscript, now housed in the same library, Malek 5980. That manuscript was copied during the poet’s lifetime, in 750 / 1349, by another accomplished scribe, Muḥammad b. ʿImrān al-Kirmānī. It too is very beautifully illuminated, and was very likely the presentation copy for the poet’s patron, the vizier Tāj al-dīn who had commissioned the collection.

Malek 5980 is thought to be the oldest extant manuscript by some 50 years. Khwājū Kirmānī is highly regarded in Iran to this day, and in 2013 a facsimile edition of Malek 5980 was produced by the University of Kerman.

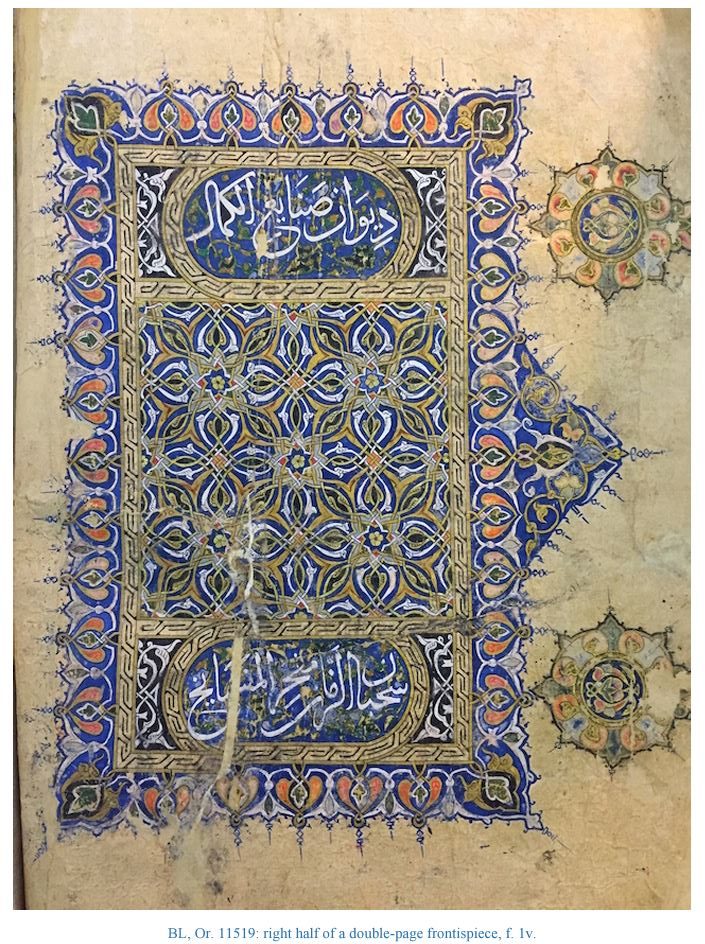

So, with this background, the reader might well imagine the excitement when the good people of the British Library delivered Ms. Or. 11519 to me in the Reading Room. On opening up the manuscript, I was confronted by a beautiful illuminated double-page frontispiece:

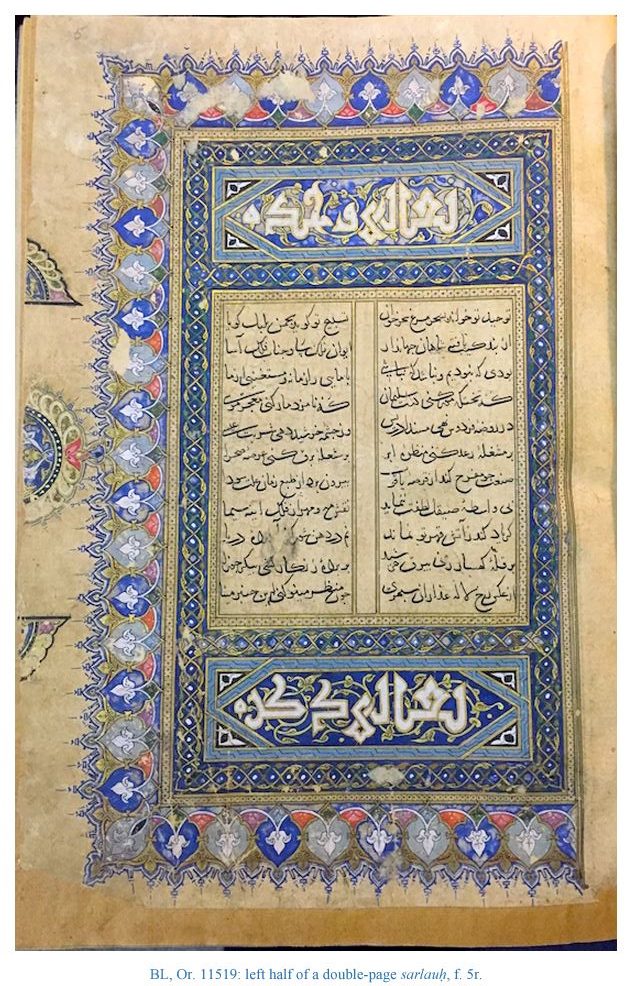

And a few folios later there is a magnificent double-page sarlauḥ:

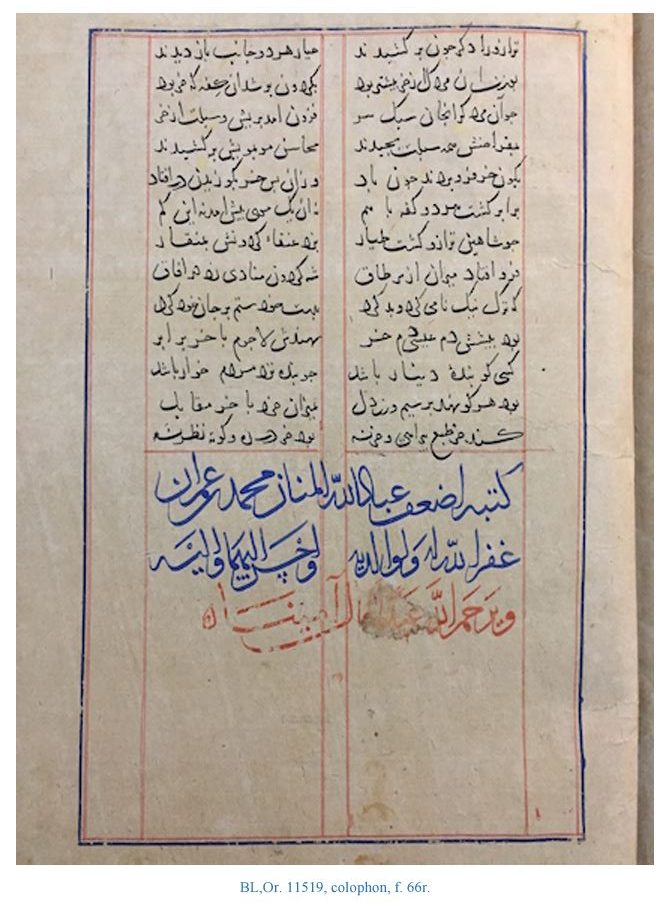

Straight away, it was clear to me that the catalogue had been in error – this was not the work of the 15th, but of the 14th century. But the hand, a beautiful Persian script (combination of taʿlīq and naskh) seemed strangely familiar to me. When I read the colophon I was amazed to find that although it was undated, the scribe named himself as Muḥammad b. ʿImrān.

No wonder I recognized the hand. There was no doubt in my mind: this manuscript must date to the mid-14th century, around the time the same scribe had copied the oldest known manuscript, Malek 5980, in 1349. As with the Malek manuscript, when Or. 11519 was copied, the poet himself was still alive and probably a resident of Kerman, along with his patron, the vizier Tāj al-dīn, and the scribe, Muḥammad b. ʿImrān Kirmānī.

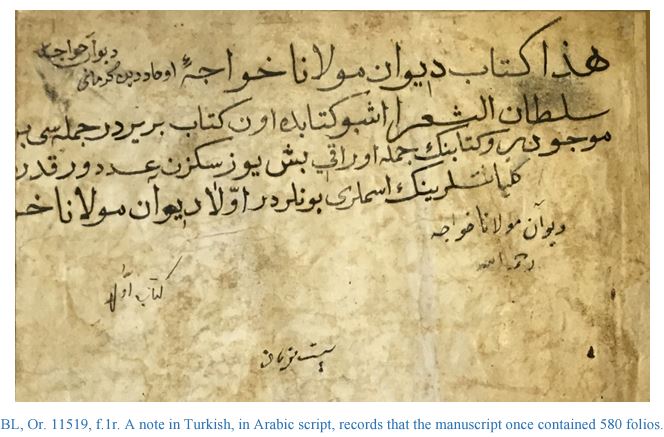

To what was Glyn Meredith-Owens referring when he said “apparently once part of a majmuʿeh [collection] of 500 folios”? There is a note in Turkish on the first folio, which says something to this effect (where the number, I believe, is not 500, but 580). Could Or. 11519 (66 folios) and Malek 5980 (352 folios) have once been part of a single manuscript? If so, do other parts remain to be discovered? These seemed intriguing possibilities.

The similarity of the illuminations and the common scribe were very suggestive. It remained for me to study the text of the BL manuscript in more detail. Ursula Sims-Williams, Lead Curator of the Persian collections, very kindly sent me photographs to enable this. I laboriously tracked down every poem by comparing the manuscript to the edition of Suhayli Khwansari (1336/1957) and to other early manuscripts, using images kindly provided by librarians in Iran. Those other early manuscripts of the Kulliyyāt of Khwājū Kirmānī:

- Tehran, Majles Library, no. 352, dated at a later time 820/1417, but I suspect it might date back to the late 14th century.

- Tehran, Golestan Palace Library, no. 335, dated 824.

- Tehran, Malek Library, no. 5963, dated 829 (the Bāysunghurī manuscript). The valuable Jalayirid manuscript of BL, Add. 18113, dated 798/1396, is older than the above copies, but since it only contains three mathnavīs, it was of little use in this comparative analysis.

As a result of my analysis, I can now say with confidence that there is no overlap in content between Or. 11519 and Muhammad b. ‘Imrān’s other Khwājū manuscript, Malek 5980. Putting all the evidence together, although Malek 5980 was previously thought to be a complete manuscript, in fact, BL Or. 11519 almost certain formed the first part of it. As such, despite the unfortunate inaccuracy in the catalogue, Or. 11519 presents a very good claim to being the earliest extant manuscript of Khwājū Kirmānī’s poetry. It is an unsuspected treasure of the Persian collection and a great gift for devotees of Khwājū Kirmānī.

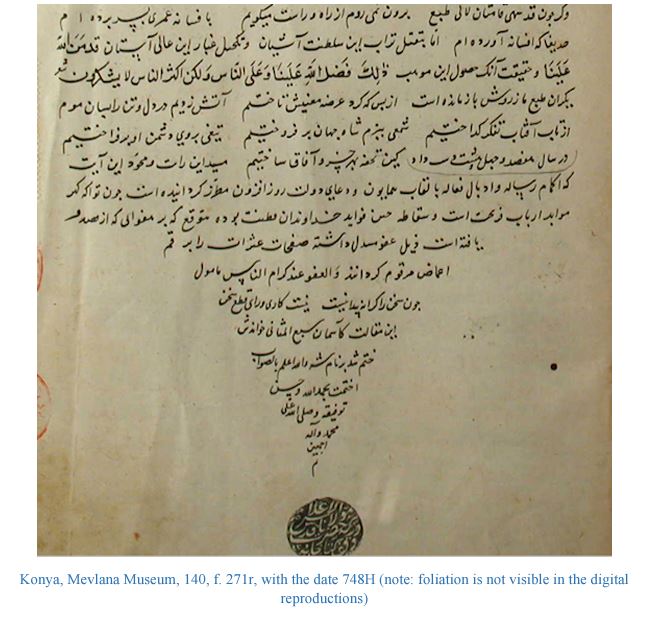

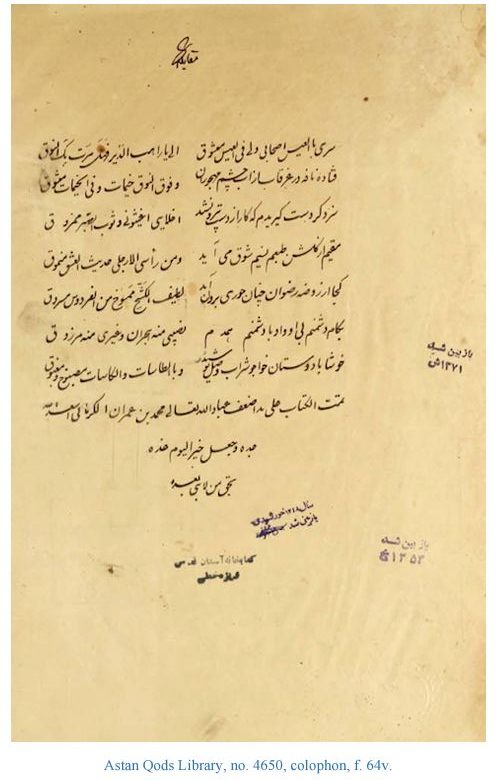

Recalling the note in Turkish at the beginning of Or. 11519 stating that the original manuscript contained 580 folios, I was determined to do what I could to track down other missing parts, with a view to reconstructing the complete works of Khwājū in its original form. My initial investigations threw up to two strong candidates and another outside possibility. Firstly, a manuscript in the Konya Mevlana Museum, no. 140, was catalogued as 748H. Secondly, a Dīvān of Khwājū Kirmānī said to be in the hand of our scribe, Muḥammad b. ‘Imrān, but catalogued as a work of the 13th /19th century, in Mashhad, Astan Qods Library, no. 4650. With the help of colleagues in Turkey and in Iran I was able to study digital images of both manuscripts. As it turned out, neither was a part of the original Khwājū ms.

For the record, and to emphasize that this kind of investigation usually involves more false leads than true ones, I find that in the Konya manuscript the date 748H mentioned on the last folio is not the data of copying but the date Khwājū finished composing the work! The manuscript was clearly copied at a later time.

As for the second promising lead, Astan Qods Library, no. 4650, turned out to be a 19th century copy, collated against Malek 5980 manuscript, written in nastaʿlīq and with a similar folio size. It records the original scribe’s signature, Muḥammad b. ‘Imrān, exactly as it appears in the original manuscript (Malek 5980), hence the catalogue entry that had caught my attention. I have not been able to determine the purpose of the copy, nor how access was gained to the old Malek manuscript; however, we know it entered the library of Mīrzā Rizā Khān Nā’īnī in 1349H / 1930 who endowed it to Astan Qods Library in (solar) 1311 / 1932.

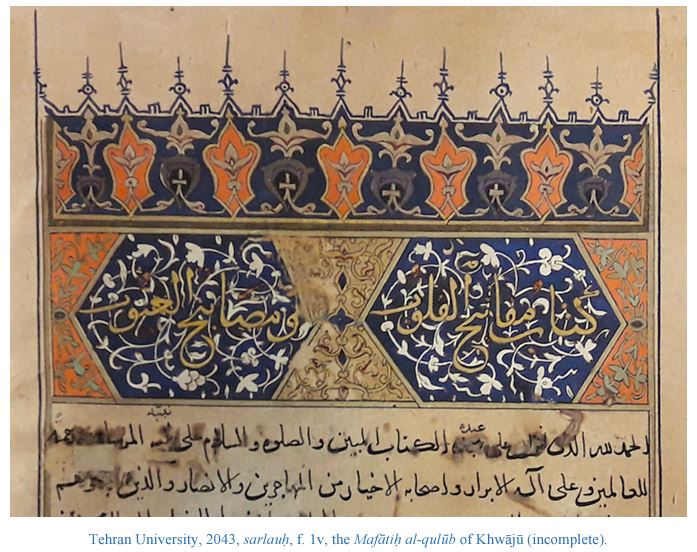

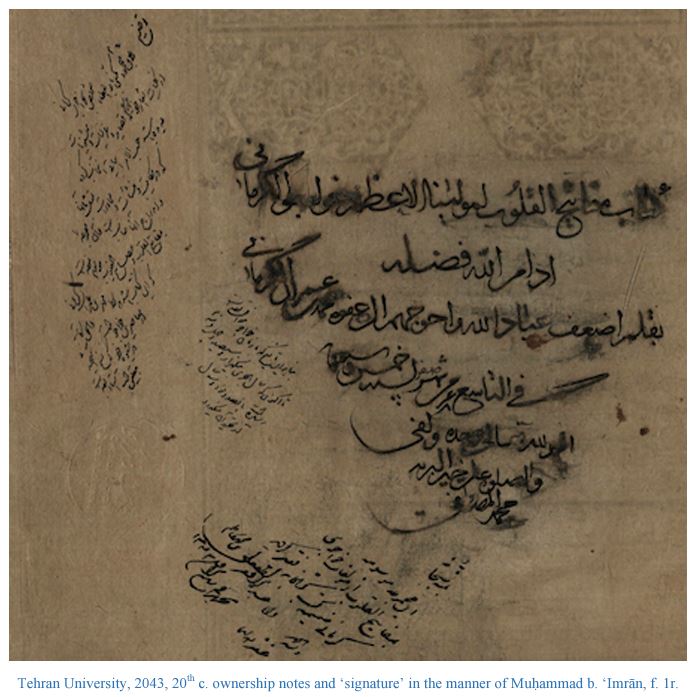

The third manuscript on my list, the outside chance, I had found catalogued as Khwājū’s Mafātiḥ alqulūb in Tehran University Central Library, no. 2043, dated 705H, and penned by Muḥammad b. ʿUmar, 44 folios. The date had to be wrong, so why not the scribe’s name? More excitement was in store. When, thanks to the generosity of the Director, I was able to examine the manuscript first hand in the Tehran University Library, I immediately recognised it was yet another part of the puzzle: here again was the same handwriting and the same style of illumination, the same paper, folio size, layout, rulings, ink, and headings.

Tehran University 2043 is incomplete at the end and so has no colophon. However, a note at the beginning of the manuscript in a similar hand to that of the scribe, provides the title of the work and the name of the scribe, Muḥammad b. ‘Imrān (not ʿUmar), as well as the year, 750 (not 705). Other notes on the same folio tells us that the manuscript was owned by Luṭf ‘Alī b. Muḥammad Kāẓim in 1343H / 1930.

Luṭf ‘Alī b. Muḥammad Kāẓim (1857-1931), known as Ṣadr al-Afāżil, was a prominent scholar and calligrapher as well as a collector of Islamic manuscripts, in a line of such men (the Nasīrī-Amīnīs). A close examination of the Tehran University manuscript convinces me that the scribe’s signature (f. 1r) is not in the hand of Muḥammad b. ‘Imrān, but is a skilful forgery. The similarities with the authentic colophons of BL Or. 11519 and in Malek 5980 suggest that whoever forged this note had seen one or both of the others colophons. Yet another note, at the beginning of Malek 5980, signed by Ṣadr alAfāżil, states his ownership of the manuscript in 1339H / 1920. The BL manuscript was presented to the British Museum by R.S. Greenshields in 1934. Of course these could all be coincidences, but the signs are that the original Kulliyyāt (of 580 folios?) – containing what would become BL Or. 11519, Malek 5980, and Tehran University 2043, and perhaps other fragments, yet to be discovered – was divided up around 1930. Since Ṣadr al-Afāżil was well aware of the worth of the original manuscript, it is also possible that the Astan Qods copy of Malek 5980 was commissioned by him around the same time, to be obtained by Nā’īnī in 1930.

A few final words on the text of the reconstructed Kulliyyāt. As stated above, I have compared the three parts of the original manuscript to three slightly later, but still early manuscripts: Bāysunghur (829), Majles (820 or earlier) and Golestan Palace (824). The results have been both interesting and complicated. The content of BL Or. 11519 is found in each of the three later manuscripts, but with poems drawn from the first section of Malek 5980 inserted into it. In each of the three later manuscripts, the poems of the first section of Malek are redistributed in different ways. Surely, BL-Malek-Tehran University should now be regarded as the core corpus against which the various later reorganisations and additions are assessed, and much work by Khwājū Kirmānī scholars remains to be done in this area. To facilitate such work, and to satisfy a demand for reproductions of high quality illuminated manuscripts from the period, it is intended that a facsimile of the BL and Tehran University manuscripts be published to complement the University of Kerman’s facsimile of the Malek manuscript (5980), published in 2013. The complexities of my textual comparisons will be provided in the introduction to the facsimile.

A version of this report will soon be published on the British Library blog.

I am grateful to the British Institute of Persian Studies for facilitating my trip to Iran.