February 2015 | BIPS Travel Grant

Following pioneering works of Hamilton (1976) and Bertram (1984) who started to explore movement patterns of the leopard Panthera pardus in eastern Africa, the species spatial ecology has been intensively reported, predominantly from its African range. Also, limited number of field studies tried to understand the Asian leopards’ ranging patterns, all from forested lowland areas. However, the scientific community still suffers from lack of proper knowledge regarding home range size and movement patterns of the leopards in west Asian rugged mountains with lower prey density where the endangered Persian leopard P.p.saxicolor persists. Their remote habitat and cryptic nature make them inherently difficult to study and past attempts have provided insufficient information upon which to base effective conservation. In order to address the paucity of basic ecological information on leopards within mountainous ranges and to explore their spatial patterns, the present investigation has been launched in Tandoureh National Park, near Turkmenistan border in northeastern Iran.

PI checking the traps’ signals in front of the first camp

Persian leopards roam across inhospitable and inaccessible terrains of Iran which make application of tracking equipment with ground-based tracking systems, such as VHF or even GSM very difficult, if not impossible. Accordingly, we used Lotek Iridium GPS collar, each supplemented with a drop off buckle with timer only option (working after 52 weeks since deployment) that automatically removes the collar so that re-capture of animals is unnecessary. Given the wide-ranging movements of leopards in Iran, ideally data acquisition would be achieved by Iridium uploads. Collars used weighed 640 g; equivalent to less than 1% of body mass for captured leopards, well below the 3% limit recommended by Kenward (2001).

Wide ranging Persian leopards are almost impossible to approach for free-darting. Therefore, we deployed foot-snares (Frank et al. 2003) and fitted with numerous modifications to minimize the possibility of injury which have been formerly proved to be safe for the leopards. As leopards are known to respond fairly to baits (du Preez et al. 2014), a killed boar was utilized to improve trapping.

Remote monitoring of snares was achieved by fitting a Telonics TBT-500 trap site transmitter (Telonics Inc., Mesa, USA) to snares to signal the triggering of traps which are checked by radio-receiver at short intervals.

Capture Operation Phase I

We initiated our project with two trap sites, both baited in September 2014. In one trap site where the boar meat was hanged from a tree, two snares were deployed to increase the chance of capture, similar to Frank et al. (2003). Also, 1-2 trailed leading to the baits were also trapped.

PI and the first leopard, Borna

During night-time, we established a base camp in higher elevations to spend between 1700 and 0900 to check traps’ signals hourly (1 to 3 km distance from the trap sites).

During eight nights of bait trapping at two sites, we had two successful captures of two adult males. Both captured leopards were in healthy situations, based on veterinary investigations and the second leopard (i.e. Bardia) was known for the past three years based on visitors’ image database we developed before capturing operation. However, Borna (first leopard) was not known to us formerly in spite of few months camera trapping efforts near the trapping site.

The second leopard, Bardia snared on its forepaw second after being darted

Capture Operation Phase II

We moved our base camp on 16 October to another place to capture the leopards, far from two previous leopards to avoid re-capturing. We spent 20 nights within the camp, but due to heavy snowfall which could cause serious threats to the team members, we had to leave the area before becoming stuck in the snow. We will re-launch the camp soon with some slight modifications.

Preliminary results

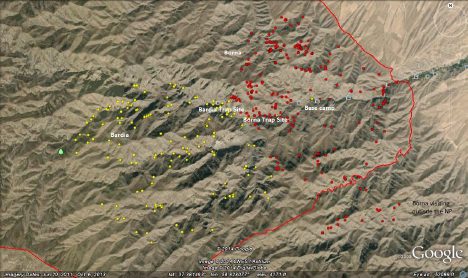

The two collared leopards show significant avoidance in their movement patterns, never enter each other’s range. Borna, the younger male twice left the National Park, approaching the nearby human communities which made us take necessary considerations with local rangers to make sure that the animal would not be poached.

The second leopard, Bardia (yellow dots) seems to be limited to his home range within the NP’s heart, never approaching the area’s boundary. From the map, we might judge that other dominant males limit movements of these two males because they never go beyond their home range.

For coming winter, we will try to capture more leopards to obtain a comprehensive snapshot about the leopards’ ranging patterns in montane landscapes of west Asia.

Recording biometric variables of the second leopard

Acknowledgement

The present project is part of Mohammad Farhadinia’s PhD dissertation in University of Oxford’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU). We sincerely thank Iranian Department of Environment for administrative support and provision of necessary permissions. MSF would like to thank Panthera for granting a Kaplan Graduate Award to procure collars. Financial support was provided by People’s Trust for Endangered Species, British Institute of Persian Studies, IdeaWild and Association Francaise des Parcs Zoologiques (AFdPZ). Also, we are grateful to Tandoureh’s game guards, particularly F.Salahshour, Gh.Pishghadam, A.Daneshfar and Barat Jalali for their field assistance.

Checking trap transmitters every one hour to make sure that the leopards do not remained inside the snare for long time

Setting up the snare trap with a bait

Departure due to heavy snowfall

Our second basecamp in high elevations

Map showing locations of two leopards during first two weeks